You’ve Heard About Energy Equity. But What About Wind Energy Equity?

Aug. 27, 2024

In 2024, a team of national lab researchers gathered perspectives from communities located near wind energy projects, like the one pictured from Bloomington-Normal, Illinois, which was co-hosted with the Prairies Rivers Network and Illinois People’s Action. Their study, which was funded by the U.S. Department of Energy's Wind Energy Technologies Office, could help create an equitable clean energy future by informing future research directions, development decisions, and government policies. Photo from Amanda Pankau, Prairie Rivers Network

Written for WINDExchange by Caitlin McDermott-Murphy, National Renewable Energy Laboratory

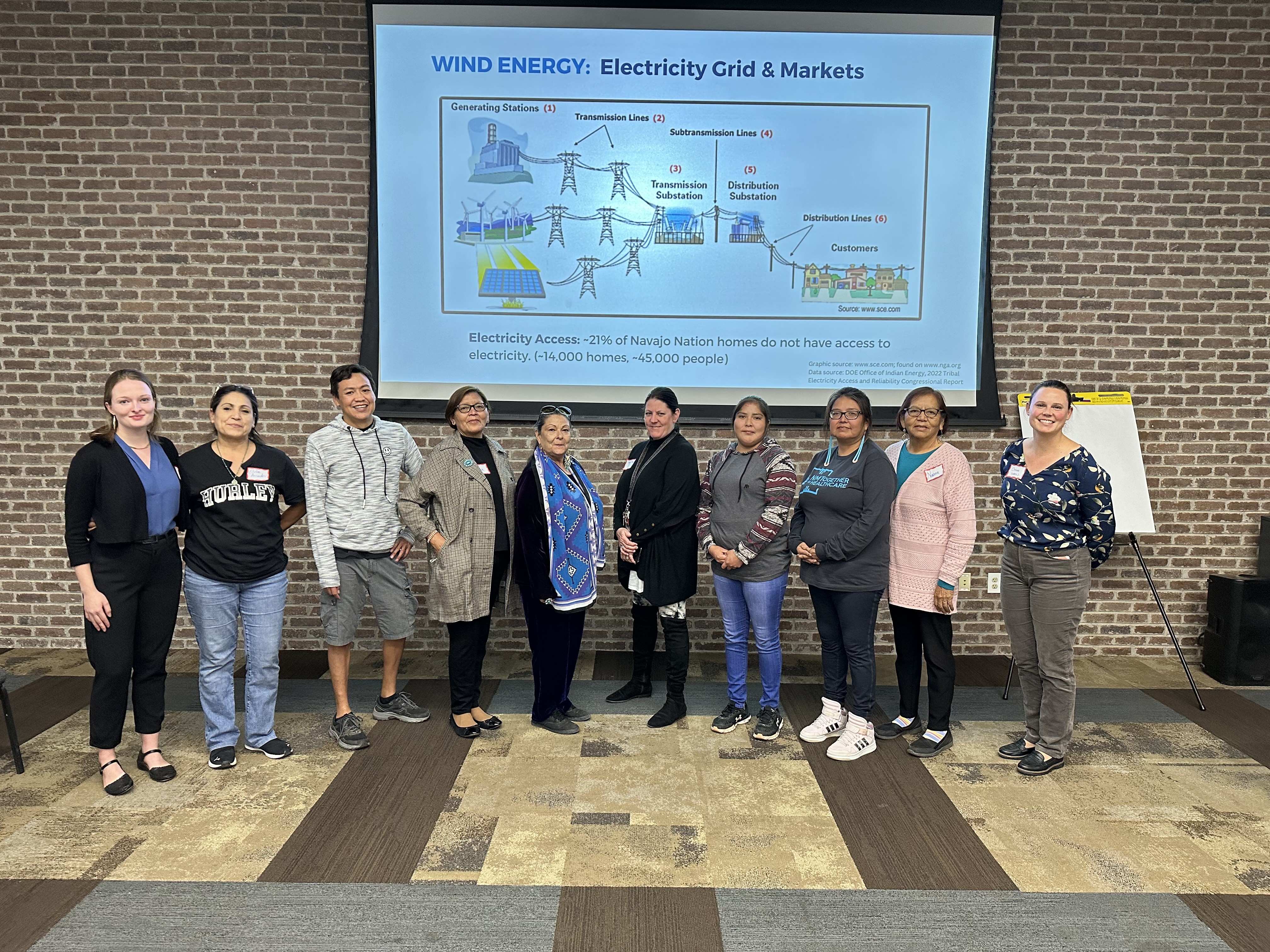

In the fall of 2023, 11 members of the Navajo Nation gathered in Gallup, New Mexico, a small town framed by red sandstone pillars. Midway through the meeting, one participant voiced a shared frustration:

“Why do we have to fight so hard for the things that other people just have?”

The Navajo Nation is still facing a health crisis caused by contaminated dust from abandoned uranium mines used for nuclear energy. Now, wind energy developers hope to build on Navajo land. And although the community members gathered in Gallup acknowledge that wind energy is “free of contaminants,” as one resident put it, distrust is hard to dislodge. The community wanted to know how these projects address their specific, local needs.

They didn’t want to see wind energy in the area just to “help someone else get rich,” one resident said.

Such concerns are not new—or limited to Gallup, New Mexico, either. In recent years, the United States has increased efforts to document, understand, and remedy the social, economic, and health impacts associated with energy development. Through the Justice40 Initiative, the government aims to equitably share the economic and social benefits associated with new clean energy development with Tribal Nations and communities that have been historically overburdened by energy-related pollution, often while not benefitting from reliable, affordable energy access. Clean energy, like land-based wind energy, might not release greenhouse gas emissions, but that doesn’t always mean its economic, social, and environmental impacts are equitably distributed across the United States.

“This is a great opportunity to connect with communities to explore and define what ‘wind energy equity’ can mean in areas experiencing wind energy development," said Clara Houghteling, a researcher at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL).

Community Voices Heard

With funding from the U.S. Department of Energy’s Wind Energy Technologies Office, Houghteling and fellow NREL researchers Anthony Teixeira and Chloe Constant set out to define what wind energy equity means. Through their multi-stage Wind Energy Equity Engagement Series (WEEES), the team first spoke to wind energy researchers, decision makers, and industry members.

The researchers have now completed the final stage of their project which includes community outreach. In the summer and fall of 2023, the team partnered with four local or regional organizations to arrange listening sessions in three different cities. Each city has been (and will likely continue to be) affected by wind energy projects. The three are:

- Bloomington-Normal, a university town in central Illinois that is surrounded by farmland and dense wind energy development.

- Elizabeth City, a small, coastal city in North Carolina that has potential for both land-based and offshore wind energy.

- Gallup, New Mexico, a majority-Indigenous community on the southeastern edge of the Navajo Nation.

“Each community brought up unique ideas that aren’t often thought about in the context of wind energy development,” Houghteling said.

The authors compiled the results of their listening sessions in a report published in March 2024 and identified a few overarching themes.

What Can Help

All three communities worried that wind energy’s economic benefits would bypass “regular people.”

Right now, Elizabeth City’s one wind farm powers data centers in another state while the city’s residents struggle to weather high energy costs and unreliable energy, including brownouts. Low-income residents in both Elizabeth City and Bloomington-Normal were more likely to bear the brunt of high energy costs. Even if these residents are not responsible for high electricity consumption, they’re often the ones who suffer for it.

The three communities also wanted more and better communication and increased community involvement. All three felt disconnected from wind energy development and left out of major decisions. In some cases, poor communication had led residents to be unaware of how wind energy projects had benefited their communities or to feel excluded entirely.

For example, in Bloomington-Normal, many residents didn’t realize that tax revenue generated from a wind farm had “saved” a local school district, according to the report. And one Elizabeth City resident said prior wind energy development felt like “an invasion.” The Elizabeth City community said the overall lack of transparency and engagement had “left a scar.”

Participants from both Bloomington-Normal and Elizabeth City highlighted the opportunity for developers to increase outreach to local schools to inspire students to consider careers in clean energy. Wind energy excites the younger generation, the residents said. If they had more opportunities to build a career in the local industry, that could help ensure a long-term connection between the host community and future development.

Each Community Is Unique

But, as Houghteling said, each community brought up their own specific concerns, too.

In Gallup, for example, many young community members are leaving to find work; residents hoped wind energy jobs might entice them to stay. But the Gallup participants’ top priority is community control. Because of their previous experiences with developers, community members don't immediately trust government officials and external companies and said they would prefer to outright own future wind energy projects. That way, they can distribute the benefits equitably throughout their community, including to those who are disconnected from the electric grid.

Folks in Bloomington-Normal, on the other hand, hoped to combat disinformation about wind energy and increase their community’s energy resilience during extreme weather events, like winter freezes. As members of an agricultural community, residents raised concerns around keeping their traditional farming lifestyle, including what happens when certain landowners have turbines on their land and others don’t. But they also saw opportunities for greater community participation, like having the local university to do research related to wind energy and agricultural interactions.

Elizabeth City residents also brought up distinctly local concerns: Many hunt—for food, not just recreation—on informal hunting grounds that include private land. Several listening session attendees asked for more research into any potential impacts on local wildlife populations and access to hunting areas. Some residents were also curious about potential financial opportunities. For example, would it make more financial sense to lease their land to a wind farm or a tree farm? Residents also noted their community is not easily persuaded to adopt wind energy to fight climate change. “Folks are just trying to get by,” one resident said.

“There is no one-size-fits-all answer to what wind energy equity means in a particular community or how to achieve it in a specific context,” Houghteling said.

And yet, common themes came through from all the communities, like:

- The importance of benefits for ordinary people.

- The need for more affordable energy rates and reduced energy burdens.

- The desire for equitable jobs and training programs.

- A call for investment in local research on environmental and community impacts.

These preliminary community conversations are already informing additional research on community benefits and wind energy regulations.

More Work To Do

Houghteling and her NREL colleagues plan to continue working directly with community members to answer more big questions related to wind energy planning and development.

They also formed a community of practice for wind energy researchers and practitioners whose work relates to equity in wind energy development. This group could help further define energy equity and justice and identify ways to address concerns in future wind energy projects.

Equity plays an essential role as the United States works to achieve carbon-pollution-free power sector by 2035 and net zero emissions economy by no later than 2050.

“Striving for wind energy equity,” Houghteling said, “requires putting the needs of communities at the front of conversations about wind energy development rather than adding them in as an afterthought.”

Check out the full report, Expanding the Baseline: Community Perspectives on Equity in Land-Based Wind Energy Development and Operations, or the study’s first, companion report, to learn more about the team’s findings. Or sign up to join the wind energy equity community of practice to share knowledge, identify opportunities for coordination, test new approaches, and identify gaps.

Learn more about wind energy equity, explore the wind energy equity map and community impacts at the U.S. Department of Energy Wind Energy Technology Office’s WINDExchange website and subscribe to the WINDExchange quarterly newsletter.

Community members, including many members of Navajo Nation, gather in Gallup, New Mexico, to discuss wind energy equity with National Renewable Energy Laboratory researchers during the Wind Energy Equity Engagement Series in an event co-hosted with the New Mexico Social Justice and Equity Institute. Photo from Anthony Teixeira, National Renewable Energy Laboratory